What is the final revelation given to Mrs. Turpin? (To state it is to statethe theme of the story.) What new attitude does the revelation impart? (How is Mrs. Turpin left with a new vision of humanity?)

What will be an ideal response?

- In the final revelation, God shows Mrs. Turpin exactly who she is: just another sinner, whose pride in her virtues must perish in eternal light. For her, the hard road toward sainthood lies ahead.

Even the hogs are fat with meanings. They resemble Mrs. Turpin, who is overweight, with eyes small and fierce, and whom Mary Grace calls a wart hog. In her perplexity, Mrs. Turpin is herself like the old sow she blinds with the hose. Her thoughts about pigs resemble her thoughts on the structure of society, “creating a hierarchy of pigs with a pig astronaut at the top,” writes Josephine Hendin in The World of Flannery O’Connor (Bloomington: Indiana UP, 1970).

Mrs. Turpin gazes into her pig parlor “as if through the very heart of mystery.” As darkness draws near—and the moment of ultimate revelation—the pigs are suffused with a red glow. Contemplating them, Mrs. Turpin seems to absorb “some abysmal life-giving knowledge.” What is this knowledge? Glowing pigs suggest, perhaps, the resurrection of the body. As Sister Kathleen Feeley says in her excellent discussion of this story, “Natural virtue does as much for fallen men as parlor treatment does for pigs: it does not change their intrinsic nature. Only one thing can change man: his participation in the grace of Redemption” (Flannery O’Connor: Voice of the Peacock [New Brunswick: Rutgers UP, 1972]).

We would be remiss not to comment that O’Connor herself would not have appreciated this question about theme. In “Writing Short Stories” O’Connor commented:

People talk about the theme of a story as if the theme were like the string that a sack of chicken feed is tied with. They think that if you can pick out the theme, the way you pick the right thread in the chicken-feed sack, you can rip the story open and feed the chickens. But this is not the way meaning works in fiction. . . . A story is a way to say something that can’t be said any other way, and it takes every word in the story to say what the meaning is. (Mystery and Manners: Occasional Prose, edited by Sally and Robert Fitzgerald [New York: Farrar, 1980].)

In a classroom, we obviously sometimes find it useful to decide upon a story’s main ideas. But meaning radiates beyond these conclusions. You might ask students about some of the meanings in “Revelation” that we could miss focusing on theme.

Joyce Carol Oates, in a comment on “Revelation,” finds the story intensely personal. Mary Grace is one of those misfits—“pathetic, overeducated, physically unattractive girls like Joy/Hulga of ‘Good Country People’”—of whom the author is especially fond. “That O’Connor identifies with these girls is obvious; it is she, through Mary Grace, who throws that textbook on human development at all of us, striking us in the foreheads, hopefully to bring about a change in our lives” (“The Visionary Art of Flannery O’Connor,” in New Heaven, New Earth [New York: Vanguard, 1974]). In a survey of fiction, Josephine Hendin also stresses O’Connor’s feelings of kinship for Mary Grace. As the daughter of a genteel family who wrote “distinctly ungenteel books,” O’Connor saw herself as an outsider: “She covered her anger with politeness and wrote about people who did the same.” In “Revelation,” Mary Grace’s hurling the book is an act of violence against her mother, for whom Mrs. Turpin serves as a convenient stand-in (“Experimental Fiction,” Harvard Guide to Contemporary Writing [Cambridge: Harvard UP, 1979]).

At least one African American student has reacted angrily to “Revelation,” calling it the “most disgusting story I’ve ever read” and objecting to “the constant repetition of the word nigger.” This is a volatile issue and involves a genuine concern. If possible, the matter should be seriously addressed in class rather than ignored or brushed aside. No one would assume that because Othello depicts several murders, it therefore endorses murder, but some students will take the occurrence of racial epithets in a story as proof of racism on the part of the author. Thus, you might begin by pointing out—or better, lead the students to point out—that while the word appears frequently in the dialogue and in Mrs. Turpin’s interior monologues, O’Connor does not employ it when speaking in her own voice: her depiction of the reflexive racism of her characters does not constitute an endorsement of racism. The use and repetition of the word nigger will inevitably create an uncomfortable atmosphere in class and may upset students; such usage is to be found in much literature of the past, as witness the constant controversy over Huckleberry Finn. But literature must be given the scope to tell the truth about human experience including its uglier manifestations, however painful the truth may sometimes be. We cannot properly come to terms with the endemic racism of America’s past (and present) by euphemising it out of our collective memory. It seems rather ironic, to say the least, that we should insist—quite rightly—that our culture is profoundly racist and at the same time seek to suppress classic works of literature for their accurate depiction of that racism.

You might also like to view...

Los animales y los pájaros de las islas son muy importantes e interesantes porque cada uno ____________________________.

What will be an ideal response?

¿Pretérito, imperfecto, presente perfecto o pluscuamperfecto del indicativo? Decide cuál de estas conjugaciones necesitas, de acuerdo al contexto. Luego completa las oraciones.Juanita no ____________________ (abrir) la ventana cuando comenzó a llover.

Fill in the blank(s) with the appropriate word(s).

¿Qué es "Conexión a Tiempo"?

A. Un programa en México que da clases gratis a los que no saben nada de la tecnología. B. Un programa en México para digitalizar los pueblos, con acceso inalámbrico (wireless) gratis para hasta quinientos usuarios a la vez. C. Un programa en México en contra del aumento de la tecnología, cuya meta es preservar la comunicación cara a cara.

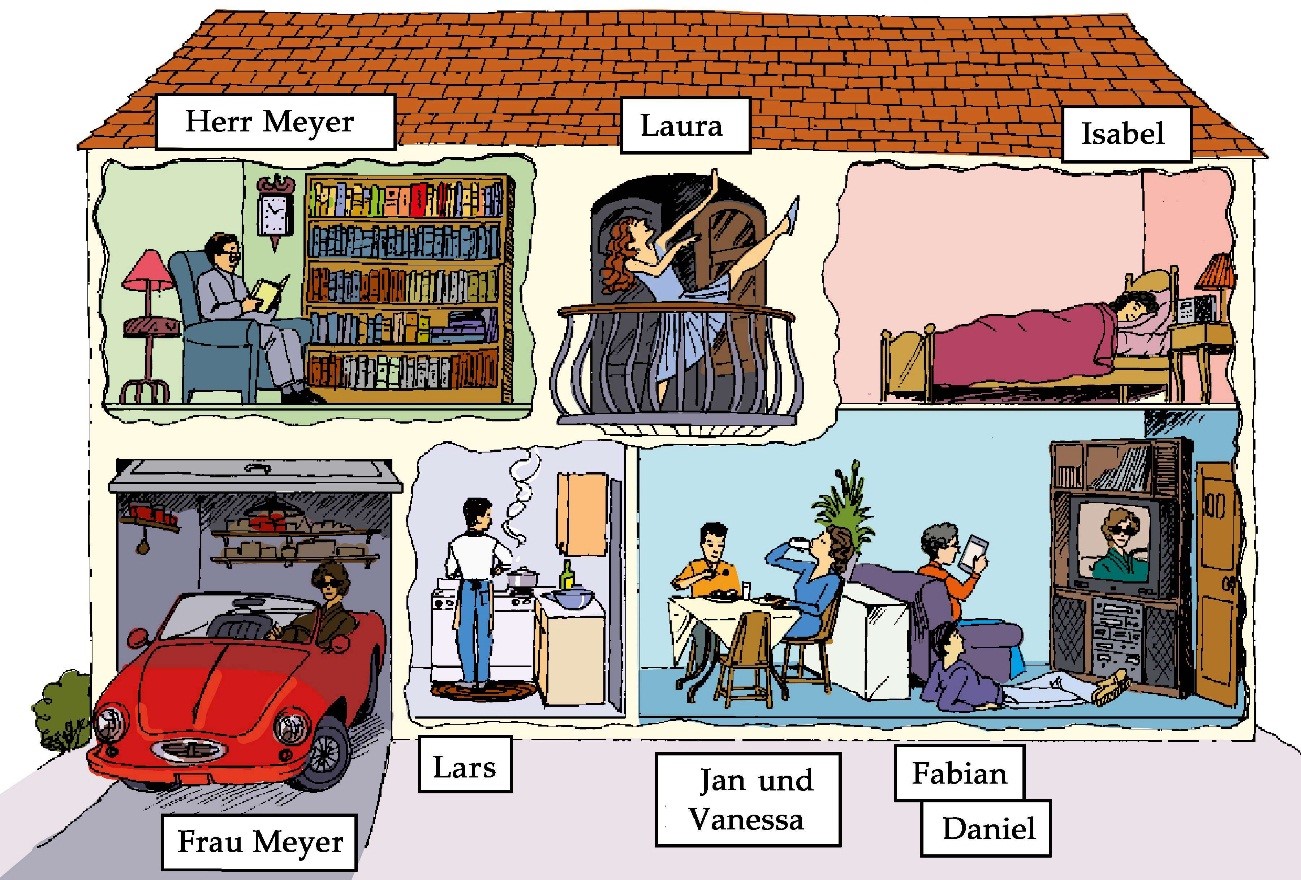

In German, identify the eight numbered objects or pieces of furniture in this house. Include the definite article with the singular and plural forms for each item. Follow the example. (16 points)

1. /

2. /

3. /

4. /

5. /

6. /

7. /

8. /