Describe the strengths and limitations of conducting secondary data analysis.

What will be an ideal response?

Each of the methods we have discussed in this chapter presents unique methodological challenges. For example, in comparative research, small numbers of cases, spotty historical records, variable cross-national record-keeping practices, and different cultural and linguistic contexts limit the confidence that can be placed in measures, samples, and causal conclusions. Just to identify many of the potential problems for a comparative research project requires detailed knowledge of the times and of the nations or other units investigated (Kohn, 1987). This requirement often serves as a barrier to in-depth historical research and to comparisons between nations.

Analysis of secondary data presents several challenges, ranging from uncertainty about the methods of data collection to the lack of maximal fit between the concepts that the primary study measured and each of the concepts that are the focus of the current investigation. Responsible use of secondary data requires a good understanding of the primary data source. The researcher should be able to answer the following questions (most of which were adopted from Riedel, 2000, and Stewart, 1984):

1. What were the agency’s goals in collecting the data? If the primary data were obtained in a research project, what were the project’s purposes?

2. Who was responsible for data collection, and what were their qualifications? Are they available to answer questions about the data? Each step in the data collection process should be charted and the personnel involved identified.

3. What data were collected, and what were they intended to measure?

4. When was the information collected?

5. What methods were used for data collection? Copies of the forms used for data collection should be obtained, and the way in which these data are processed by the agency or agencies should be reviewed.

6. How is the information organized (by date, event, etc.)? Are there identifiers that are used to identify the different types of data available on the same case? In what form are the data available (computer tapes, disks, paper files)? Answers to these questions can have a major bearing on the work that will be needed to carry out the study.

7. How consistent are the data with data available from other sources?

8. What is known about the success of the data collection effort? How are missing data indicated? What kind of documentation is available?

Answering these questions helps ensure that the researcher is familiar with the data he or she will analyze and can help identify any problems with it.

Data quality is always a concern with secondary data, even when the data are collected by an official government agency. The need for concern is much greater in research across national boundaries, because different data-collection systems and definitions of key variables may have been used (Glover, 1996). Census counts can be distorted by incorrect answers to census questions as well as by inadequate coverage of the entire population (Rives & Serow, 1988). Social and political pressures may influence the success of a census in different ways in different countries. These influences on records are particularly acute for crime data. For example, Archer and Gartner (1984) note, “It is possible, of course, that many other nations also try to use crime rate fluctuations for domestic political purposes—to use ‘good’ trends to justify the current administration or ‘bad’ trends to provide a mandate for the next” (p. 16).

Researchers who rely on secondary data inevitably make trade-offs between their ability to use a particular dataset and the specific hypotheses they can test. If a concept that is critical to a hypothesis was not measured adequately in a secondary data source, the study might have to be abandoned until a more adequate source of data can be found. Alternatively, hypotheses or even the research question itself may be modified in order to match the analytic possibilities presented by the available data (Riedel, 2000).

Measuring Across Contexts: One problem that comparative research projects often confront is the lack of data from some historical periods or geographical units (Rueschemeyer, Stephens, & Stephens, 1992; Walters, James, & McCammon, 1997). The widely used U.S. UCR Program did not begin until 1930 (Rosen, 1995). Sometimes alternative sources of documents or estimates for missing quantitative data can fill in gaps (Zaret, 1996), but even when measures can be created for key concepts, multiple measures of the same concepts are likely to be out of the question; as a result, tests of reliability and validity may not be feasible. Whatever the situation, researchers must assess the problem honestly and openly (Bollen, Entwisle, & Alderson, 1993).

Those measures that are available are not always adequate. What remains in the historical archives may be an unrepresentative selection of materials from the past. At various times, some documents could have been discarded, lost, or transferred elsewhere for a variety of reasons. “Original” documents may be transcriptions of spoken words or handwritten pages and could have been modified slightly in the process; they could also be outright distortions (Erikson, 1966; Zaret, 1996). When relevant data are obtained from previous publications, it is easy to overlook problems of data quality, but this simply makes it all the more important to evaluate the primary sources. Developing a systematic plan for identifying relevant documents and evaluating them is very important.

A somewhat more subtle measurement problem is that of establishing measurement equivalence. The meaning of concepts and the operational definition of variables may change over time and between nations or regions (Erikson, 1966). The value of statistics for particular geographic units such as counties may vary over time simply due to change in the boundaries of these units (Walters et al., 1997). As Archer and Gartner (1984) note,

These comparative crime data were recorded across the moving history of changing societies. In some cases, this history spanned gradual changes in the political and social conditions of a nation. In other cases, it encompassed transformations so acute that it seems arguable whether the same nation existed before and after. (p. 15)

Such possibilities should be considered, and any available opportunity should be taken to test for their effects.

A different measurement concern can arise as a consequence of the simplifications made to facilitate comparative analysis. In many qualitative comparative analyses, the values of continuous variables are dichotomized. For example, nations may be coded as democratic or authoritarian. This introduces an imprecise and arbitrary element into the analysis (Lieberson, 1991). On the other hand, for some comparisons, qualitative distinctions such as simple majority rule or unanimity required may capture the important differences between cases better than quantitative distinctions. It is essential to inspect carefully the categorization rules for any such analysis and to consider what form of measurement is both feasible and appropriate for the research question being investigated (King, Keohane, & Verba, 1994).

Sampling Across Time and Place: Although a great deal can be learned from the intensive focus on one nation or another unit, the lack of a comparative element shapes the type of explanations that are developed. Qualitative comparative studies are likely to rely on availability samples or purposive samples of cases. In an availability sample, researchers study a case or multiple cases simply because they are familiar with or have access to them. When using a purposive sampling strategy, researchers select cases because they reflect theoretically important distinctions. Quantitative comparative researchers often select entire populations of cases for which the appropriate measures can be obtained.

When geographic units such as nations are sampled for comparative purposes, it is assumed that the nations are independent of each other in terms of the variables examined. Each nation can then be treated as a separate case for identifying possible chains of causes and effects. However, in a very interdependent world, this assumption may be misplaced; nations may develop as they do because of how other nations are developing (and the same can be said of cities and other units). As a result, comparing the particular histories of different nations may overlook the influence of global culture, international organizations, or economic dependency. These common international influences may cause the same pattern of changes to emerge in different nations; looking within the history of these nations for the explanatory influences would lead to spurious conclusions. The possibility of such complex interrelations should always be considered when evaluating the plausibility of a causal argument based on a comparison between two apparently independent cases (Jervis, 1996).

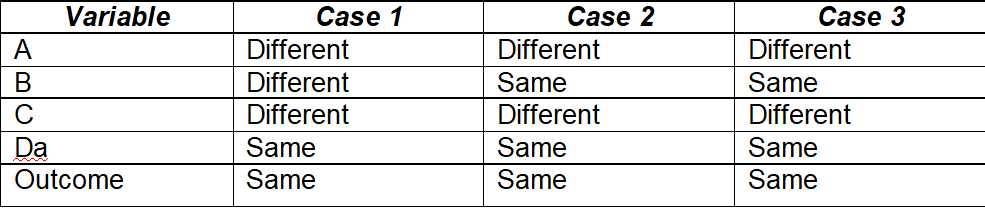

Identifying Causes: Some comparative researchers use a systematic method for identifying causes, developed by the English philosopher John Stuart Mill (1872), called the method of agreement. The core of this approach is the comparison of nations (cases) in terms of similarities and differences on potential causal variables and the phenomenon to be explained. For example, suppose three nations that have all developed democratic political systems are compared in terms of four socioeconomic variables hypothesized by different theories to influence violent crime. If the nations differ in terms of three of the variables but are similar in terms of the fourth, this is evidence that the fourth variable influences violent crime.

The features of the cases selected for comparison have a large impact on the ability to identify influences using the method of agreement. Cases should be chosen for their difference in terms of key factors hypothesized to influence the outcome of interest and their similarity on other, possibly confounding factors (Skocpol, 1984). For example, in order to understand how unemployment influences violent crime, you would need to select cases for comparison that differ in unemployment rates so that you could then see if they differ in rates of violence (King et al., 1994).

Exhibit 9.6 John Stuart Mill’s Method of Agreement

aD is considered the cause of the outcome.

Method of agreement A method proposed by John Stuart Mill for establishing a causal relation in which the values of cases that agree on an outcome variable also agree on the value of the variable hypothesized to have a causal effect, whereas they differ in terms of other variables

You might also like to view...

Social media based "peer-to-peer" bullying more harmful than the older face-to-face schoolyard version

Indicate whether the statement is true or false

In a chi-square test, the larger the difference between expected and observed frequencies, the more likely you are to _____

a. choose to use a t ratio or some other parametric test b. reject the null hypothesis c. retain the null hypothesis d. use the median test

Some studies suggest that ______students may become more delinquent upon failing in school because the expectations to succeed are higher for them than for working-class students.

a. middle class b. upper class c. middle and upper class d. lower and middle class

Approximately _____ criminal victimizations occur each year

A) ?5 million B) ??10 million C) ??15 million D) ??20 million