How does the policy trilemma help to explain the failure of Argentina's currency board?

What will be an ideal response?

In the early 1990s, Argentina's commitment to capital mobility and to the one-peso-equals-one-dollar exchange rate fostered optimism. When that optimism was challenged by the peso crisis in Mexico, the Argentine people became aware that the soundness of the banking system was in their hands. The combination of fixed exchange rate and capital mobility prevents the central bank from conducting an independent monetary policy, such as providing needed liquidity to protect bank deposits. Instead, the regime relies on foreign creditors to step in when citizens lose confidence in the banks. This worked well enough in the mid-1990s, but it became increasingly obvious that Argentina's economy could not grow unless the peso was devalued, so that exports and domestically-produced import substitutes could compete with global products. Because the currency board did not allow for devaluation, either it or capital mobility would have to end.

You might also like to view...

In a communist economy,

A. the state controls the means of production. B. individuals decide what to produce, how to produce it and who gets it. C. economic decisions are decentralized. D. the market system is used to allocate resources.

Changes in government spending and/or taxes as the result of legislation, is called

What will be an ideal response?

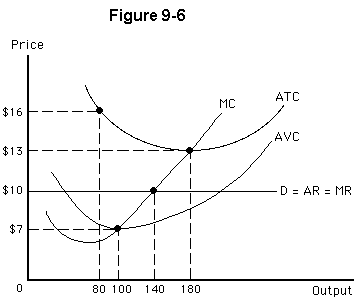

Figure 9-6 shows the marginal cost and average total cost curves for a perfectly competitive firm. This firm will

a.

earn an economic profit

b.

suffer an economic loss in this long-run situation

c.

suffer an economic loss in the short run and close

d.

break even if it expands to 180 units of output

e.

suffer an economic loss and continue producing in the short run

A shift of the demand curve to the left represents

A. an increase in demand. B. an increase in quantity demanded. C. a decrease in quantity demanded. D. a decrease in demand.