How do you evaluate the situation of SpainSko, S.L. in December 1994? What is your diagnosis? Please make it explicit

What will be an ideal response?

A quick look at the profit and loss statement in case Exhibit 4 shows that SpainSko lost 4,395,181 pesetas in 1994. This is close to 50 percent of the startup funds (10 million pesetas) the Goyes declared to have available to launch SpainSko. What may be even worse, these heavy losses have been incurred in spite of the fact that no salaries have been charged to the company. In other words, Pilar, Gonzalo, and their sons have been working at no cost to SpainSko, S.L. Had they collected a reasonable salary, the losses would have been even worse!

How far away was SpainSko from turning a profit in 1994? To fully compensate for a total loss of 4,395,181 pesetas, an additional 610 pairs of shoes (4,395,181/7,200) should have been sold in 1994. In other words total sales volume should have been 217 + 610 = 827 pairs of shoes. In 1994, SpainSko sold 217 pairs, which was just 26 percent of break-even volume! With these contribution margins and with this level of expense, to break even SpainSko would have to increase its efficiency by a factor of 3.8 times.

This also means that they cannot afford similar direct marketing actions in 1995, because if they were to capture another 187 customers, buying 217 pairs as they did in 1994, plus the repeat purchases of the first 187 customers (187 × 16 percent = 30 pairs), sales in 1995 would be some 217 + 30 = 247 pairs, and they would still lose more than 4,000,000 pesetas.

In other words, as Cesar Icochea, a student at IESE, put it, “If they continue like this, they will soon run out of funds, without attaining break even.” In fact, if they were to continue like this, they would run out of funds by 1996. Therefore, modest increases in marketing efficiency will not do! They must radically change their marketing procedures; they must find ways to capture new customers at a much lower cost!

Put another way, if they capture 200 new customers per year, at a cost of some 4,000,000 pesetas per year, it would cost them some ten to twelve years and a total investment of 40 to 48 million pesetas to reach the sales volume necessary for SpainSko to break even!

Why?

Instructors may now wish to turn the question around and present students with the following dilemma:

Let’s assume, for the time being, that we accept the 1994 level of expenses as given. Let’s also imagine that, somehow, SpainSko has captured a certain customer base, and that the company stops attempting to capture any new customers; that they concentrate in just maintaining and repeat selling Dansko shoes to this

customer base. How large a customer base should SpainSko have captured in order to be able to break even just by (repeat) selling to this hypothetical customer base?

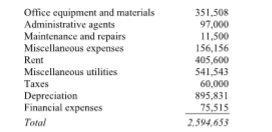

In this case, the company would spend hardly any money in advertising, and there would probably be no travel expenses. We would be left with the following “other expenses” (from the 1994 Profit & Loss Statement):

How much does it cost SpainSko to generate one repeat purchase from an existing customer base? Assume a customer base of 100 customers. SpainSko would have to do two mailings per year to them, at a cost of 100 × 2 mailings × 64 pesetas each = 12,800 pesetas. SpainSko would generate a 16 percent response rate; that is, it would sell 16 pairs of shoes to these 100 customers. Therefore, the cost of selling one pair of shoes to an existing customer base would be 12,800 ÷ 16 = 800 pesetas per pair sold, and the net contribution margin would be 7,200 – 800 = 6,400 pesetas.

To compensate for the calculated level of other expenses, SpainSko would have to sell 2,594,653 ÷ 6,400 = 405 pairs of shoes.

To sell 405 pairs of shoes as repeat purchases in any one year to an existing customer base, such customer base would have to be made up of 2,531 customers so that a repeat purchase rate of 16 percent on a customer base of 2,531 customers would yield a volume of sales of 405 pairs of shoes. This is the amount of sales necessary to pay for the level of SpainSko overhead expenses with no attempt to capture any new customers, but limiting itself to just maintaining and selling to this customer base.

In other words, if somehow or other the Goyes succeeded in creating a customer base of about 2,531 customers, and concentrated in just extracting repeat purchases from them, they would break even at the level of contribution margins and overhead expenses incurred in 1994.

We should bear in mind, however, three issues: (a) The above level of expenses still would not include any salary for Pilar or anybody else. (b) These sales would not generate any funds that might be devoted to capturing new customers, either for company growth or to replace dormant customers. (c) This is the sales volume necessary to break even; that is, it would not generate any profits to compensate for previous years’ likely substantial set-up or new business launching losses. Therefore, the real important matter is to find out if the Goyes can build up a customer base of 2,531 customers before they run out of the 10 million pesetas of capital funds they seem to have available to invest in the new venture.

Before we attempt to answer this question by means of a marketing plan, we should first determine a diagnosis. And to do this, we should look more closely at the different marketing actions designed and implemented in 1994, to see if any of them could provide the kind of efficiency SpainSko needs in capturing new customers.

As can be seen in Exhibit 1, in 1994 SpainSko spent 3,427,167 pesetas in various marketing actions that produced 92,897 impacts, with a yield of 217 pairs of shoes sold. This is an average cost of 36.9 pesetas per impact, and 15,793 pesetas spent per pair.

Out of all these marketing actions we can arbitrarily pick and choose (see Exhibit 2) the ones which had a below average cost. Six specific actions with a cost of 803,748 pesetas generated 126 pairs sold, at an average cost of 6,379 pesetas per pair. This last figure looks much closer to the rule of thumb used by Alfred Frank, when he said that, out of the total amount paid by the end buyer, about one third should cover the invoiced price to be paid to the manufacturer of Dansko shoes, another third was to be used to pay for advertising and promotions, and the last third should pay for overhead expenses and profits of the importer-distributor.

If SpainSko could spend four times 803,748 pesetas = 3,215,000 pesetas to generate four times 126 orders = 504 pairs of shoes sold, SpainSko might reach break-even level, as roughly calculated at the bottom of Exhibit 2.

The real question, of course, is whether this is at all possible, given the fact that these “efficient” marketing actions, or at least some of them, look very artisan-like, hand made, and not very massive. For instance, it is not very likely that Gonzalo and Pilar may be able to come up with a further list of 1,500 friends of the family, in addition to the list of 500 friends already used in 1994. In other words, possible direct marketing actions should not only be cost efficient, but should also be volume effective; that is, capable of delivering an absolute high volume of sales.

Leaving a few brochures in the lobby of the AIED was highly cost efficient, but it seems unlikely that SpainSko can substantially increase the absolute number of pairs sold in this way.

We may now be in a position to attempt a diagnosis of SpainSko in December 1994:

SpainSko seems to be a potentially viable new business venture, with a good but peculiar product, which is likely to attract a diffuse segment of consumers not easily identified and captured. In the first ten months of 1994, the company has used a number of direct marketing actions (basically mailings and magazine brochure inserts, followed up by personal availability to incoming telephone calls).

In spite of there being some reason for using each specific action, it looks as if 1994 has been the year of testing, with a lot of trial and error going on.

The 1994 economic results are very negative, with substantial losses. It seems fairly obvious that SpainSko cannot go on like this. It is imperative that, in order to reach break-even volume before running out of startup cash (10 million pesetas), the company has to substantially improve its efficiency (cost per new customer captured) and its effectiveness (absolute number of new customers captured by means of each direct marketing action).

So far, capturing new customers has proved to be very expensive, but this business seems to have one major advantage: once a new customer has been captured, there seems to be a high probability of repeat purchases over a fairly long period of time associated with the low cost of maintaining this active customer base. Just maintaining and serving the right size customer base could be potentially very profitable.

Therefore, the major challenge facing SpainSko seems to be how to build its active customer base up to around at least 2,530 end users of Dansko shoes in Spain without running out of the remaining funds available. Alternatively, SpainSko should identify marketing actions capable of delivering new customers at a cost of around 6,400 pesetas each or lower, which would allow them to grow their customer base without increasing their investment for that purpose.

Actual sales in various Central European countries seem to indicate that there should be enough market potential in Spain to eventually sell some 3,000 pairs of Dansko shoes per year.

There seems to be some hope that SpainSko can do this in two ways:

a. Carefully selecting the kinds of direct marketing actions that have resulted in capturing new customers at a reasonable cost in 1994. (See Exhibit 2.)

b. Carefully exploring some of the new potential direct marketing actions, as mentioned at the end of the case. It would be wise not to commit substantial funds to test any new action. Tests should be small, and relatively high amounts of funds should be committed only after a particular kind of marketing action has demonstrated its capacity to generate new customers with efficiency and effectiveness.

Therefore, Gonzalo and Pilar Goyes should carry on and continue operating, and should not fold up SpainSko and quit.

You might also like to view...

Which of the following service quality dimensions refers to employee competency with respect to knowledge and courtesy?

A) service reliability B) service assurance C) extended services D) customer empathy E) appearance

The Atlas conversion factor is the arithmetic average of the current exchange rate and the exchange rates in the two previous years. Incomes measured by the Atlas conversion factor are generally more stable over time and changes in income rankings are more likely to be due to relative economic performance than fluctuations in the exchange rate.

Answer the following statement true (T) or false (F)

A single-echelon inventory system ______.

a. is one where each supply chain partner (echelon) sequentially forecasts demand b. reduces potential for the bullwhip effect c. is one where supply chain partners forecast demand as a single group d. reduce information flows

The Charade Corporation is preparing its Manufacturing Overhead budget for the fourth quarter of the year. The budgeted variable manufacturing overhead is $5.00 per direct labor-hour; the budgeted fixed manufacturing overhead is $75,000 per month, of which $15,000 is factory depreciation.If the budgeted direct labor time for November is 7,000 hours, then the total budgeted manufacturing overhead for November is:

A. $110,000 B. $125,000 C. $95,000 D. $75,000